Index for this Article:

Introduction

Introduction

Avoiding Retraumatization while Recovering Feelings

Avoiding Retraumatization while Recovering Feelings

Defensive Responses to Trauma

Defensive Responses to Trauma

Fear, Trembling and Transformation

Fear, Trembling and Transformation

Neurogenesis

Neurogenesis

Excerpts from chapter 22 in the Revised Complete Guide to Acupressure

by Iona Marsaa Teeguarden, M.A., L.M.F.T., © 2002, Japan Publications, Tokyo/NY

Painting and Photo by Mehdi Naimi

Painting and Photo by Mehdi Naimi

|

After the appalling attack on the World Trade Center -- which for me came on the heels of harassment by neighbors and a life-threatening riding accident -- I was often reminded that an ancient Chinese curse was: "May you live in interesting times!" When things get too interesting, in a way that threatens our life or sense of security, the times are traumatic and the result often is anxiety and a state of hyperarousal, or the tendency to be easily alarmed.

Trauma can be caused not only by life-threatening events, but also by events which we perceive as putting ourselves or loved ones at risk. Basically, trauma means that the organism enters a state of shock and is physiologically altered by it. A hallmark of shock trauma is hyperarousal, or the inability to moderate arousal. At an extreme, the autonomic nervous system is activated much of the time and everything is seen as a threat, but the symptoms of hyperarousal can also be subtle. According to the DSM-IV, they include:

- hypervigilance or hyperalertness

- exaggerated startle response

- difficulty falling or staying asleep

- difficulty concentrating or memory impairment

- irritability or outbursts of anger.

It helps to understand that hyperarousal is a normal adaptation to abnormal events. Hyperarousal is a common reaction after a threatening or catastrophic event such as a natural disaster (flood, earthquake, hurricane, tornado), fire, shooting, vehicle accident, physical or sexual attack, or act of war or terrorism.

This is called "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder" (PTSD) if: 1) two or more of the above symptoms are present and persistent, 2) the condition follows experiencing or witnessing "an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others," and "the person's response involved intense fear, helplessness or horror," and 3) the symptoms go on for more than a month. (During the first month after the trauma, the hyperarousal is called "Acute Stress Disorder.")

Characteristic of a stress disorder is persistently reexperiencing the traumatic event - in thoughts, images, perceptions or dreams. There may also be flashbacks, intensifying the feeling that the traumatic event is recurring. On the other hand, there may be 'dissociative amnesia,' or an inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma.

Bodymind distress is intensified by things identified with the traumatic event, so activities, places, people and feelings associated with the trauma are avoided when possible. Also, intimacy may be avoided because of the fear that others can't be trusted. Often there is a sense of detachment or estrangement from others. There may be a feeling of not wanting to be here, or just a lack of the feeling of wanting to be here, and this can lead to substance abuse and other self-destructive behavior.

Top of Page

Top of Page

Often there is a numbing of general responsiveness and a constriction throughout the body, so that the range of emotion is restricted. However, hyperarousal can also include hypervigilance regarding body sensations, and this can intensify chronic pain problems or lead to somatization disorder (i.e. multiple and confusing physical complaints).

Trauma involves intense shock. The Qi flow is blocked by muscular tension. If the tense position is maintained, the tension becomes armoring. Because the muscles are bound up, the person often doesn't get enough deep sleep to nourish the body tissues. Therefore, a traumatic history often underlies chronic pain problems, sleep disorders, chronic fatigue syndrome, psychosomatic illnesses, immune disorders and fibromyalgia - a chronic pain condition in which there are multiple "tender points," like in the neck, shoulders and lower back. . . .

[The key symptom of PTSD is being more easily alarmed - hyperarousal and hyperalertness.] . . . A threat need not be life-threatening to trigger the hyperalertness, because we tend to startle and scare more easily than we normally would. [After the trauma, the body is exhausted but often we cannot surrender to fatigue, because of the feeling that we have to be ready for another threat. As we become more tired, we are more easily frightened.] It's like the entire bodymind system is on overdrive. We are hypervigilant, yet it is difficult to concentrate, because of the toll which the trauma and stress has taken. Despite our diligence, threats and losses may continue to occur, making it harder to distinguish between paranoia and appropriate fear.

Repetitive thoughts about and images of the threat or attack are normal, but they can add to our fatigue. Remembering or reexperiencing part of the traumatic event can bring up the same feelings that we had at the time, and this can be draining.

- When you notice yourself going into a stressful spiral, take a deep breath, and remind yourself that 'in this moment, I am okay." Appreciate just being okay right now.

- Remember that there are people worse off than you. This might sound like focusing on the negative, but actually is a reminder to focus on what is positive in your life [on what you still have and still can do].

See page 313 (in the book) for eighteen other "Remedies for PTSD & the Exhaustion Phase of the Stress Response."

Top of Page

Top of Page

The Shriek, 1895

Edvard Munch

|

Repetitive thoughts and images may be a clue that we need to process the traumatic event, when we have enough stability and support, so that it gets put into long-term memory. However, the first project is learning to contain the feeling(s) and "switch channels," focusing on feelings like competence or comfort, so as to avoid feeling overwhelmed and retraumatized. . . (For more about switching channels, see page 308. . .)

Avoiding Retraumatization while Recovering Feelings

Today, in work with trauma survivors, a common caution is to avoid retraumatization, because it intensifies the symptoms of hyperarousal. Twenty years ago, a common therapeutic approach with abuse issues was encouraging the 'victim' (or 'survivor') to relive the experience and exaggerate emotional reactions like crying, sobbing, shouting and screaming. Certainly, emotional catharsis can be releasing. However, reliving traumatic events can also be retraumatizing. . .

The 'kindling' hypothesis explains that repeated stimulation can result in a decreased capacity to modulate physiological arousal, so that the nervous system becomes more excitable and more easily activated. Therefore, the person is more easily retraumatized. In this state of hyperarousal or the inability to modulate arousal, a traumatic memory or violent movie can cause the heart rate to become significantly elevated - and it doesn't go down right away. Similarly, a nonspecific noise can cause a traumatic nightmare.

Another part of the physical response to hyperarousal is the secretion of an enormous amount of endorphins. Animals who are severely and chronically stressed have physiological states similar to that of dependence on high levels of opium or morphine. [Dr. Bessel Van der Kolk theorizes that this may be] why battered women often keep finding abusive men. If they are in a fight, then opiates are secreted and a numbing reaction sets in. Feeling numb may seem comfortable, so it can be addicting.

To feel is to heal. To heal from PTSD, we need to recover the ability to feel - but we also need to avoid retraumatization. A simple way to start is by writing about the traumatic experience, in a journal or in letter form. While describing what happened, notice what you feel. Make notes like "that's when I started feeling scared (or paranoid, hypervigilant, angry, hurt, ashamed, etc.)." Also notice where you feel the feeling(s) in your body, and hold points in that area. Find out whether there are changes in breathing, or body sensations like trembling or shaking (which can be the body's way of completing the emotional sequence that was interrupted by the need to constrict the body and restrict the feelings). Just visit some part of the traumatic event; don't stay there too long. If tears come, or if your throat feels achy or your lips tremble, allow yourself to cry, even if it seems to go on and on. Crying is a normal part of the grieving process and a natural part of recovering the ability to feel.

Top of Page

Top of Page

When the range of feeling and emotion has been restricted, positive emotions have been suppressed too, and they need to be nurtured. A simple way to do this is to look for a place of comfort in the body - perhaps in the chest or abdomen, or even just a finger or toe - and really notice the comfortable feeling. Another way to nurture positive feelings is to recall an experience of competence, and notice where you feel that empowerment in your body.

Whenever you recall part of a traumatic event, go back to the comfortable or competent feeling. This helps both to avoid retraumatization and to restore what was lost in the traumatic experience. It is a way of reprogramming the bodymind, so that we can remember how to feel comfortable and competent. Another simple way is to take a deep breath and feel the relief of a threat being even temporarily past. Relief is an important and underrated feeling. With it comes an appreciation of being alive, of the senses, of life itself. As Dr. Hans Selye said, the 'attitude of gratitude' is one of the best antidotes to distress.

To unthaw physically and emotionally, we need to allow and recognize feelings which were frozen in our musculature. One of the safer ways to do so is with JSD acupressure, because it helps us feel our muscular tensions while balancing the Qi (energy), and it brings us back into our bodies. Returning to the body is an antidote to dissociation.

Bodywork enhances the ability to feel body sensations. Jin Shin Do® Acupressure particularly helps recover the ability to feel. Holding distal points at the same time as tense or blocked local points makes it easier to feel and release the tension or armoring. Holding tense points for several minutes tends to bring consciousness into that body part, and sometimes also into feelings or emotions which the tension helped us suppress. This effect is enhanced when verbal body focusing techniques are used to help clients feel into blocked places and focus on the 'felt body sense,' being open to any thoughts, feelings, colors, images or sensations that might come up. . .

Top of Page

Top of Page

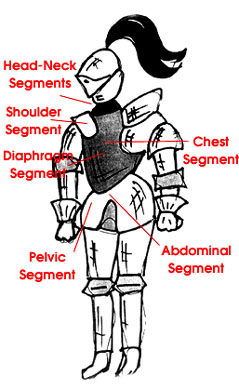

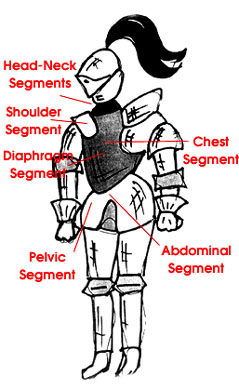

"The Armor Segments"

Illustration by Emilio Perotti, Italy

|

Defensive Responses to Trauma

The fight-or-flight response to trauma is well known. Another common response, and one which can be equally effective, is to freeze. When the trauma is such that one feels impotent or powerless, and the defense mechanisms of fight and flight are blocked, then freezing may be the only remaining option. When no immediate escape is possible and the emotion is overwhelming, we often 'numb out,' or lose touch with our feelings. The mind shuts down, and we become dissociated from reality. Things may seem to be happening in slow motion, or we may even be unconscious.

At the time of the trauma, freezing can be a great survival tool. Physically freezing, or remaining motionless, can save our lives in situations where one more step could bring disaster, or one little noise could invite attack. Many animals employ the defense mechanism of freezing, because most predators recognize prey by their movements, and may bypass an animal which is motionless. The opossum is best known for feigning death when attacked, as reflected in the phrase 'playing possum,' which is defined as pretending to be asleep, dead, ill or unaware. During trauma, we don't have to pretend to be unaware, because dissociation and shutting down feelings are normal parts of the shock response.

However, immobility also means constriction of the organism. Freezing means that the fight or flight response has been thwarted. The energy which would have been discharged by fighting or fleeing is bound up in the nervous system. After the threat has passed, animals generally discharge this energy through muscular movement or sound, and then return to normal functioning. In human beings, the highly developed neocortex can override completion of instinctual responses, and feelings like fear, anger, hatred and rage can build up until they overwhelm the nervous system and we collapse or freeze again.

A main problem with maintaining the frozen posture is that it requires chronic muscular tension, which does not help us feel healthy and happy. When parts of the body are immobilized for a long time, or if mobility is extensively limited, this affects circulation - not only of blood and lymph, but also (and first) of Qi or energy. Jin Shin Do sessions are indicated, because two main aims of JSD are releasing tension and balancing energy.

Chronic tension or armoring is the eventual result of freezing without fully unthawing. This armoring could be in any or all of the body segments (described in chapter two). To find out where your body is tense or frozen, it could be interesting to take a few deep breaths and check inside, taking a little trip down through the segments. Notice where you feel tension, blockage, soreness or numbness. (You can also hold those points.)

. . . Courage is acting in spite of fear, including by doing whatever is necessary to survive. If flight is not possible, then freezing can be a healthy response to trauma. However, staying frozen and shut down is not healthy, even if it feels safe. When we are shut down, the trauma is shut in. It is still present in our muscular tension, body posture, defensive attitudes, and tendency to hyperarousal. By gradually thawing out enough to feel the fear and other feelings, we can realize how really hard it was to survive the traumatic experience. This paves the way to appreciating ourselves for having survived.

(For more about switching channels, see page 308 [and pages 317-322 in

"A Complete Guide to Acupressure, Revised."])

Top of Page

Top of Page

Fear, Trembling and Transformation

. . . The Nei Ching says that "in times of excitement and change" the Kidneys create fear and trembling. After a threat has passed, animals move out of the frozen state through a trembling discharge. They literally "shake it off." Their so-called superiors, human beings, are often not so wise.

This reminds me of an incident last summer with my rodeo horse, "Freddy." Although flight is the main defense mechanism of the equine species, Freddy has several times chosen the intelligent response of freezing rather than panicking in a situation from which he cannot escape without help, and which threatens life or limb.

One morning I awoke to see Freddy standing still in the middle of two acres of arena and pasture, with his front legs splayed out. This posture can be a sign of colic (a bad tummy ache from which a horse can die), so I ran out there in my pajamas to find that Freddy had somehow stepped in the middle of a highway cone which I had used for a riding lesson. His foot had broken through the side of the plastic cone, and it was stuck on his leg. I was afraid that he had seriously hurt his leg and might be lame, but he had only minor abrasions and some swelling. He probably had tried to get the cone off his leg, then determined that he'd better stay put until help arrived and started telepathically calling for me. (I do think he does that!) Flight would have led to more injury, not escape.

After getting the cone off his leg, I put a halter on Freddy and walked him to see if he was sound, then led him out of the pasture. After doing cold packs for the swelling, I let him loose in a small grazing area and did some acu-points, figuring that it couldn't hurt and might help. While I was holding points in the shoulder and leg, I remembered that trembling is a natural way of releasing trauma. I realized that Freddy might not have had time to tremble. Instead of leaving him alone after freeing him from the cone, I had walked him immediately, in my panic to find out if he was sound.

As I reflected on this, I felt and saw a big shudder go through his shoulder and leg muscles! I continued to hold points on his leg periodically, until the veterinarian arrived (for his scheduled semiannual visit!). The muscular trembling occurred several more times, but none as dramatic as the first. Freddy "shook it off" as soon as he could, and holding the points helped him relax enough to feel the tensions that he needed to shake off.

In JSD sessions, sometimes clients will tremble or shake when muscular armoring releases. This can be a primarily physical reaction. There can be little trembling sensations as the breath moves into body areas which had been frozen. As we thaw out, or emerge from the immobility of chronic tension, there can also be surges of feeling or emotion, which need to move through us. Some feelings, like fear, can be released through trembling or shaking, so it is wise to welcome and allow these release phenomena. Feelings like grief, hurt and sorrow want to find an outlet through tears. Anger and rage need to be released through physical activity, perhaps including exercises like [the Qigong movement called] "Punching with Angry Eyes."

Photo credit: Mehdi Naimi

Photo credit: Mehdi Naimi

|

First, we need to feel the way that the body has been frozen. In JSD sessions with a practitioner we trust, as we feel cradled and supported, it can become pleasurable to allow ourselves to feel immobile. It can become safe to gradually feel the places where the body has been frozen and numb. This may be partly because the stimulation of acu-points induces the secretion of endorphins, which can produce an analgesic effect stronger than morphine. As we get a felt body sense of how immobility was part of our reaction to trauma(s), we can sense how the body can unwind or emerge from the frozen state. . .

[One of the experiences through which I became particularly impressed with] trembling as a release mechanism [was] during a class with Maryanna Eckberg, Ph.D. She led us through an exercise demonstrating a somatic approach to the treatment of traumatic shock. First she suggested that we briefly recall a traumatic experience, noticing the body feelings that came with the memory. I remembered walking against the current of knee-high water during a flood in 1997, when my son and I evacuated. I felt fear in a way I couldn't at that time, because then I couldn't lay down, relax, and feel my belly trembling. Some of the fear had not been processed, though I had channeled much of the adrenal energy into fighting for restoration of the creek and levees.

Dr. Eckberg next suggested that we recall some experience in which we felt competent and powerful, noticing the body feelings that accompanied the experience of competence. I remembered a successful barrel racing experience. (This is a horseback event involving running really fast on horseback while making tight turns around three barrels, in a cloverleaf pattern.)

After we had time to enjoy feeling competent, Dr. Eckberg suggested we return to the traumatic experience. Again, I felt the fear and experienced belly trembling. As we went back and forth between the traumatic experience and the competent feeling, there was less emotional response with the traumatic memory, and more awareness of the pleasant feelings accompanying the experience of competence. The exercise ended with the latter, which is important because we need to remember how to return to feelings of competence and comfort after the threat is past. . .

Top of Page

Top of Page

Neurogenesis

As a good friend said recently, "I know whatever doesn't kill us makes us stronger, but do we have to be this strong?" It can be encouraging to realize that a side effect of recovery work is neurogenesis, or brain growth. Ericksonian hypnotherapist Ernest Lawrence Rossi (author of The Psychobiology of Mind-Body Healing) said in a lecture that neurogenesis results from three main things: 1) novelty (a new kind of approach), 2) environmental enrichment (including of the inner world), and 3) physical exercise (or a heightening of physical sensations). Any reputable PTSD therapy involves all three.

Dr. Rossi said that a key to supporting neurogenesis is staying in touch with that which is fascinating and tremendous about what's happening. This is easier when what's happening seems positive. When what's happening seems negative, then noticing positive synchronicities is a way to stay in touch with what is fascinating.

For example, when I was in the frustrating process of dealing with Monterey county officials in an attempt to stop environmental destruction and ongoing harassment by neighbors, my mom's minister from North Dakota twice called when I was in the blackest night of the soul. The synchronicity of these calls was fascinating and helped me feel that I was being supported and guided through this stressful time, which was more difficult because of a trail riding accident that knocked me unconscious and landed me in the hospital for over two weeks. (Murphy's Law in action? Everything takes longer than you expect, and sometimes whatever can go wrong, will!)

. . . We know the stress is really bad when we've forgotten to laugh for a while. Being able to laugh is a means to emotional transformation, and it is a sign that Shen (the core inner spirit) is more happily at home. Remember to value and contact the people who somehow, magically, tend to get you laughing again.

The Revised Complete Guide to Acupressure © 2002, which includes the entire Posttraumatic Stress Disorder chapter, by Iona Marsaa Teeguarden, is available through:

Homepage

Homepage Articles on Jin Shin Do ® Articles on Jin Shin Do ® Healing After Trauma Healing After Trauma

Top of Page

Top of Page

Copyright © 1999 - 2013 Jin Shin Do® Foundation.

All rights reserved.

|

Painting and Photo by Mehdi Naimi

Painting and Photo by Mehdi Naimi

Photo credit: Mehdi Naimi

Photo credit: Mehdi Naimi